By: Jafe Arnold

By: Jafe Arnold

From the Indo-Europeans to the ‘New World’

he world’s diversity of cultures has successfully defied the “globalization” of the Atlanticist, Liberal, unipolar “End of History” scenario proclaimed in the 1990’s. It is increasingly recognized both de facto and de jure that we are in transition towards a multipolar world order. The historic drama of this process is not always appreciated for what it is: we are on the way towards a world order promising unprecedented cooperation between civilizations based on the refusal of hegemony of any one state, ideology, and identity. From the point of view of international relations, political science, geopolitics, and indeed the history of civilizations, this is a revolution.

he world’s diversity of cultures has successfully defied the “globalization” of the Atlanticist, Liberal, unipolar “End of History” scenario proclaimed in the 1990’s. It is increasingly recognized both de facto and de jure that we are in transition towards a multipolar world order. The historic drama of this process is not always appreciated for what it is: we are on the way towards a world order promising unprecedented cooperation between civilizations based on the refusal of hegemony of any one state, ideology, and identity. From the point of view of international relations, political science, geopolitics, and indeed the history of civilizations, this is a revolution.

In the modern world, we also often forget to appreciate the original meaning of words. “Revolution” is usually etymologically traced back to Latin revolutio, or “the act of revolving”, meaning a radical change aimed at restoring an original position in a cycle. However, “revolution” as a word and concept can be pursued not only even further back to Greek verbs meaning “to wind around” or “to enfold,” but the Latin, Greek, and other Indo-European linguistic expressions of “revolution” all trace back to the original Proto-Indo-European root welh- or kʷel- literally meaning “to turn” or “to rotate” but more often than not connoting “surrounding.” The original Indo-European term encompasses the origins of the concept of “revolution” as it would be derived in all the complex understandings of the Indo-Europeans’ descendant languages and cultures, among which Greek and Latin are prominent European cases. [1]

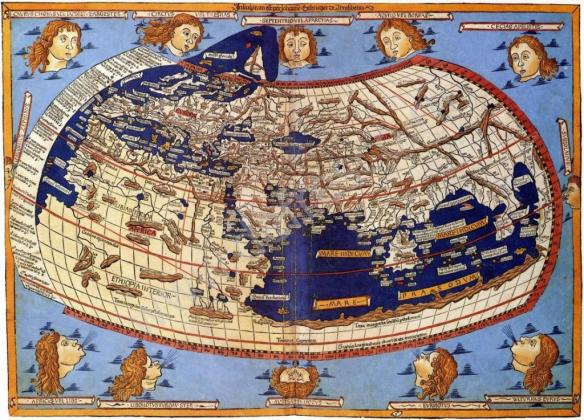

The Indo-European homeland and linguistic evolution a la Anthony

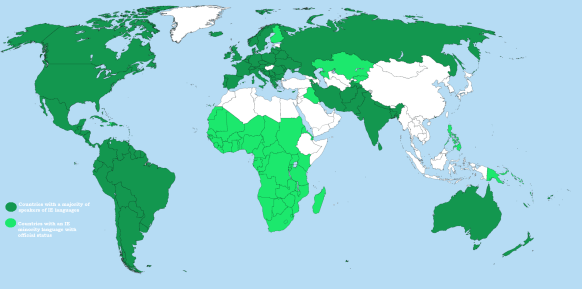

Indo-European languages in 21st century Eurasia

Global distribution of Indo-European languages by state

The original Proto-Indo-European set of terms that would yield “revolution” referred to the most important aspects of life for the original Indo-European people: war (the military maneuver of “surrounding” an enemy, which vanquishes a threat and therefore “returns” the cosmic balance), pastoral life (the cycle of herding and grazing livestock, the cattle cult sacrifice cycle in their cosmogony), and the celestial-divine (the gods “surrounding” men with powers, protection, tribulations, the celestial cycles, etc.). The Proto-Indo-European kʷel- is also the root for the word “wheel”, or kʷékʷlos, which was of supreme importance to the Proto-Indo-Europeans’ view of the cosmos and their historical movement: the wheel or circle of the cosmos and life is predominant in Indo-European mythologies and it was thanks to the Indo-Europeans’ domestication of the horse (another linguistic correspondence: h₁éḱwos) and their utilization of wheel and chariot technology that allowed them to spread across the globe, with which they left a primordially and still relatively similar cultural and linguistic sphere stretching from the European peninsula to the Indian sub-continent (hence the 19th century term “Indo-Europeans”). These are not merely intriguing linguistic observations: the Indo-European conceptual and linguistic roots of “revolution” have informed many of the earth’s cultures’ understanding of such complex concepts as radical change, “revolving order”, or “restoration.” That these roots or significations have been denied or lost does not mean that they do not exist.

What does this have to do with multipolarity? Multipolarity, as a revolution, is of both the past and the future: it is a radical negation of Atlanticist, Liberal, unipolar modernity in favor of a new international system and it is a restoration of or return to the world’s natural diversity of civilizations, identities, and ideologies. Continue reading

he rise of the protest movement in Donbass (and other regions of historical Novorossiya) which resulted in the proclamation of the People’s Republics, was a reaction to the coup d’etat in Kiev and aggressive Russophobic policies. It is no accident that the first legislative step of the new Ukrainian authorities was abolishing the language law, ratified in 2003 by the Verkhovna Rada in line with the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which effectively pushed the Russian language out of the educational and cultural-information space of Ukraine. However, the popular movement in Donbass at the end of winter and spring 2014 also had deeper motives. The proclamation of the people’s republics of Donbass was a logical reaction to the dismantling of Ukrainian statehood as it had been formed in the framework of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The new Ukrainian authorities violated the tacit social contract of loyalty to the existing state in exchange for a guaranteed minimum of cultural-linguistic rights for the regions of the “South-East” (historical Novorossiya).

he rise of the protest movement in Donbass (and other regions of historical Novorossiya) which resulted in the proclamation of the People’s Republics, was a reaction to the coup d’etat in Kiev and aggressive Russophobic policies. It is no accident that the first legislative step of the new Ukrainian authorities was abolishing the language law, ratified in 2003 by the Verkhovna Rada in line with the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which effectively pushed the Russian language out of the educational and cultural-information space of Ukraine. However, the popular movement in Donbass at the end of winter and spring 2014 also had deeper motives. The proclamation of the people’s republics of Donbass was a logical reaction to the dismantling of Ukrainian statehood as it had been formed in the framework of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The new Ukrainian authorities violated the tacit social contract of loyalty to the existing state in exchange for a guaranteed minimum of cultural-linguistic rights for the regions of the “South-East” (historical Novorossiya).

y including the processes and event-related phenomenon “Russian Spring,” “war,” and “statecraft” in the title of this article, I am by no means implying any kind of intellectual provocation or attempting to realize a political order. On the contrary, the intended position here can be associated with the existence of millions of people who have in one way or another engaged (during wartime) in the creation of a completely distinct region, a will and fate of more than just one century tied to the fate of the Russian world.

y including the processes and event-related phenomenon “Russian Spring,” “war,” and “statecraft” in the title of this article, I am by no means implying any kind of intellectual provocation or attempting to realize a political order. On the contrary, the intended position here can be associated with the existence of millions of people who have in one way or another engaged (during wartime) in the creation of a completely distinct region, a will and fate of more than just one century tied to the fate of the Russian world.

By: Alexander Gegalchiy – translated by Jafe Arnold

By: Alexander Gegalchiy – translated by Jafe Arnold